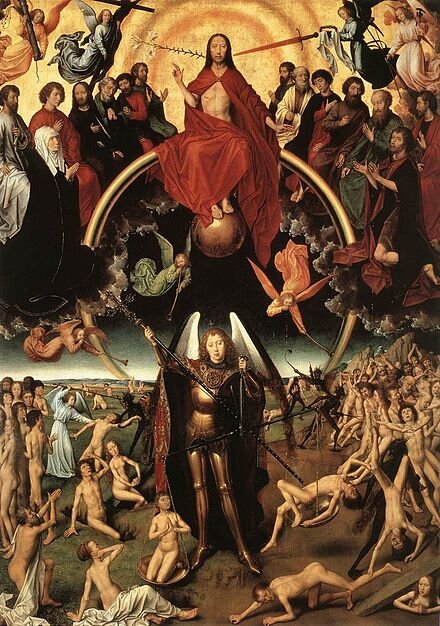

“Dies irae, dies illa… teste David cum Sibylla.”

Day of wrath, that day, … as David witnessed with the Sibyl.

Wait … who exactly was this Sibyl? And why does she show up in the Requiem mass but not anywhere else in scripture or the liturgy? Early Music Monday continues with part 2 of Sacred or Secular this week!

Dies Irae

It’s Requiem season, so this week’s Early Music Monday takes a peek at the Dies Irae chant. Not only is it one of the most frequently used melodies in all of western classical music, the text walks a very fine line between sacred scripture and pagan imagery… but more about that next week!

Who murdered Leclair?

An unsolved mystery for Early Music Monday - who murdered Jean-Marie Leclair? Was it the ex-wife or his nephew?

Thomas Weelkes

“He literally peed on his boss and showed up to work drunk all the time and he never lost his job. How good do you have to be as an organist/composer to behave like that?!”

How to read chant notation

Next up in Early Music Monday, a quick and dirty guide to reading neumes and chant notation! There are many different opinions on the “right” way to perform chant, but the basics of how neumes should be read are the same for all of them.

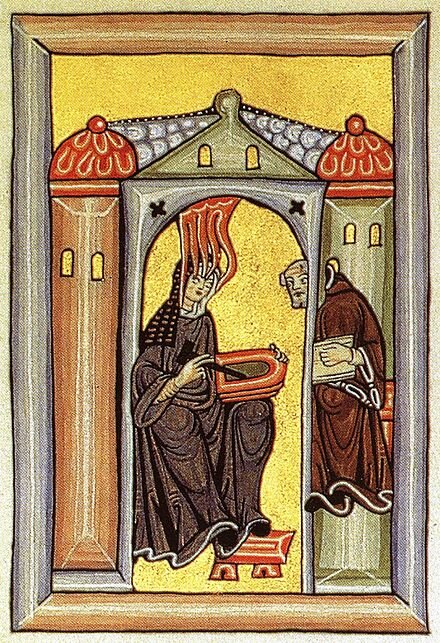

Hildegard von Bingen

In a time when women had few rights and little power, Hildegard von Bingen corresponded with popes and emperors, invented her own language, oversaw a Benedictine convent, and is considered by many to be the founder of the study of natural history in Germany. Oh, and her music is pretty awesome too…

Modes in the 16th and 17th centuries

Confused about psalm tones and modes? Our friends at Early Music Sources have an excellent video explaining why this is such a tricky topic.

Litanies de la Vierge

Last week’s Early Music Monday post was about original pronunciation. What happens when you combine original pronunciation with historically informed performance practices? This. And this is why I sing!

Original Pronunciation

Today’s Early Music Monday is all about words! Just as original pronunciation of Shakespeare’s English reveals rhymes and hidden puns and brings the language to life, playing early music with an understanding of styles and practices from that time brings the music to life and shows off details that would otherwise be missed.

Sprezzatura

An Early Music Monday post for Labor Day! Here’s the origin of the idea that a performer (athlete, actor, etc.) should “make it look easy” while doing something incredibly difficult. For an added bonus, it might help keep you alive in the always complicated royal court…