Oh Dowland…

- couldn’t get a court post in England

- traveled through Germany insulting the court lutenists

- penned multiple “get off my lawn” diatribes

- also happened to compose, occasionally

Come hear our program on Friday!

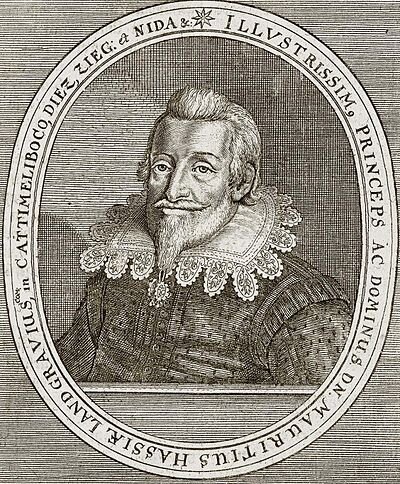

Moritz, Landgraf von Hesse-Kassel

This week’s Early Music Monday post comes from Kassel, Germany! Landgrave Moritz of Hesse-Kassel was patron to Heinrich Schütz and John Dowland (among others), built the first permanent theater in Germany, and liked to stir up religious controversy.

Dowland's "A pilgrimes solace"

These program notes were written by Elise Groves and Karen Burciaga for a program of selections from Dowland’s “A Pilgrimes Solace” for voices, viols, and lutes presented by Long & Away, a consort of viols on March 24, 2018.

English lutenist John Dowland (1563-1626) spent nearly half of his life working and traveling in Europe and chasing an elusive position with the musicians of the English royal court. He first moved to France at age 17 in the service of the English Ambassador to the French King. After returning to England, Dowland was involved with musical entertainment for Queen Elizabeth, though he did not have an official position. On one of these occasions - the Queen’s visit to Sudeley Castle in 1592, a scene was prepared in which My heart and tongue were twinnes was performed by ‘one who sung and one who plaide.’ Encouraged by this success, Dowland applied for a position as one of the royal lutenists in 1594. He was unsuccessful (though no one was actually hired) and decided to return to the Continent, intending to travel to Italy and study with Luca Marenzio.

He went first to Wolfenbüttel to the court of the Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg. Then he, along with a group of musicians from that court, traveled to Kassel to the Landgrave of Hesse. Eventually Dowland continued onward to Italy while the others returned to Wolfenbüttel, along with a letter from the Landgrave to the Duke:

“[Dowland] is a good composer. If, as Your Grace writes, he has belittled your lutenists, and has scorned them in any way, he apologizes most humbly and sincerely for it.”

Once Dowland reached Florence, he became acquainted with a group of English Catholics living in exile who were conspiring to overthrow Queen Elizabeth and put a Catholic back on the English throne. While Dowland had been raised as a Protestant, he converted to Catholicism while in France. At this point, he must have realized the magnitude of the risk he was taking. His trip abroad was intended to improve his reputation so he could obtain an English royal appointment. Being linked to treasonous expats was unlikely to help, so he quickly abandoned his plan to study with Marenzio and returned to Kassel. He also sent a letter to one of his English patrons in which he confessed his bitterness over the rejection by the royal court, and then explained everything that had happened in Italy, even naming names, in hope of getting back in the good graces of the Queen.

In 1596 Henry Noel encouraged Dowland to return to England, saying that the Queen herself had been asking about him and wishing for his return. Thinking that Noel would assist him in obtaining a court position, he returned to England to discover that Noel had died. Dowland commemorated his patron with the Lamentatio Henrici Noel and also published The First Booke of Songs, to great success. In 1598, after failing again to join Queen Elizabeth’s musical establishment, he was hired by King Christian IV of Denmark. Dowland completed The Second Booke of Songs and The Third and Last Booke of Songs while in Denmark. He returned to England briefly in 1603-1604 to see about obtaining a court position with the newly crowned James I (whose wife, Queen Anne, was the sister of Christian IV). He dedicated Lachrimae or Seaven Teares to Queen Anne, but was unsuccessful once again and went back to Denmark.

Dowland’s last published book, A Pilgrimes Solace, was published in 1612 shortly after he returned to England from his fourteen-year stint in Denmark. His music was well-known at this time; the books of songs were constantly being reprinted, his solo lute music was in the repertoire of most advanced players, and many of his pieces had been arranged either by him or by his contemporaries (Byrd, Morley, etc.) for other instruments and groupings. Dowland’s name appeared in theatrical works, proving that he was well-known and well-respected as a composer and a musician, even after so many years abroad.

In contrast to his success and reputation, Dowland wrote cruelly of his fellow musicians, attacking in particular ‘simple Cantors, or vocall singers’ who excel in ornamentation but are ignorant of theory, as well as young ‘professors of the Lute’ who do not respect their elders, and ‘divers strangers from beyond the seas’ who claim the English ‘have no true methode of application or fingering of the Lute’. In particular, he singled out Tobias Hume, who claimed that the lyra viol was equal to the lute for both solo repertoire and accompaniment.

These attacks contain a contain a certain amount of “get off my lawn” along with the appearance that Dowland was lashing out at anyone and anything, likely because of his deep unfulfilled desire to obtain an English court position. He wrote frequently of the unfairness with which he had been treated, and one can see how his frustration over this issue was expressed in his music. Frustrations about the inconstancy of women or deep mourning over the wrongs one had experienced (both real and imagined) have always been common poetic topics, but these, along with the popularity of the cult of melancholia, gave Dowland ample space to vent his feelings as he saw fit. Certainly rivalries, criticism, rejection, and general frustration were as known to musicians then as they are now, but it would seem that what we describe as “professionalism” may not have been one of Dowland’s virtues.

In any case, sometimes the squeaky wheel gets the grease. In 1612 an extra position was created increasing the number of court lutenists from four to five. This position was given to Dowland, finally granting him his long-sought English royal appointment at the age of 49.

A Pilgrimes Solace follows the pattern set by his earlier Bookes of Songs or Ayres and Lachrimae, all containing 21 or 22 songs, and all of which were “table-books” meant to be placed flat on a table with the musicians gathered around all sides. Like his previous books, this music can be played by any number and combination of voices and instruments (Dowland recommends viols and lutes). In contrast, though, this remarkable collection breaks his previous pattern and offers four very distinct styles of music: strophic, dance-inspired songs on the subject of love; mournful Italianate solos; somber contrapuntal works on religious themes; and allegorical masque-like songs.

In pieces such as Disdaine me still and Stay time a while, we hear of cold-hearted ladies and spurned lovers, heartfelt pleas and frustrated hopes. These works are clearly based on Renaissance dance forms, many of them triple-time galliards such as Shall I strive, which we perform along with its instrumental counterpart from Lachrimae (Henry Noels Galliard). The boisterous coranto Were every thought an eye presents singers with the challenging task of fitting all the text into a very intricate, upbeat rhythm! Next in the collection are several solo songs in a more modern Italianate character, all quite woeful in mood. Set for solo voice, treble viol, and continuo, Goe nightly cares is one example of the “new” declamatory way of setting text that English composers were only just beginning to warm to in the first decades of the 17th century.

Perhaps the emotional core of A Pilgrimes Solace, and of this evening’s performance, are several religious texts set for four voices. We have chosen to vary the instrumentation within the trilogy (Thou mightie God) to highlight different textures and moods within each part. These heartfelt pieces employ daring harmonies, long phrases with unexpected suspensions, and imitation between voices, as is clearly heard in the opening of When Davids life. Also in this group are In this trembling shadow with its wrenching opening and closing harmonies, and If that a sinners sighes, which we present as a solo song.

The final pieces of the collection are dramatic tunes, some jovial and some melancholy, possibly for use at masques or court entertainments rather than home music-making. All feature gods and allegorical figures, with a story set in 1-3 verses followed by a “Conclusion” that drives home a moral point. My heart and tongue were twinnes, published in A Pilgrimes Solace even though it had been written much earlier, is in this group, even though it explores the familiar subjects of music and love.

We chose to supplement these wonderful works with a few selections from Dowland’s other publications. Our opening piece, Cleare or Cloudie, comes from The Second Booke of Songs or Ayres of 1600, which followed shortly after his highly popular and influential First Booke. This volume was also the first appearance of his hit song “Flow My Tears” which has inspired generations of composers; indeed Dowland himself composed seven complex instrumental settings of the tune and published them in Lachrimae or Seaven Teares. From this seminal work we offer Lachrimae Amantis (“Lover’s Tears”), John Langtons Pavan, Mrs Nichols Almand and the aforementioned Henry Noels Galliard.

No concert of Dowland’s works could be complete without hearing some of his lute music. Tonight we present The Lady Laitons Almane paired with My Lord Chamberlaine his Galliard, which was composed “for two to plaie upon one Lute”; we have left it to our lutenists to decide the best course of action.

The closing piece of this evening’s program, I shame at mine unworthines, comes from the second edition of a celebrated and enormous collection of verses penned by Sir William Leighton called Teares or Lamentations of a Sorrowfull Soule, which he compiled for Prince Charles in 1614 apparently while in debtor’s prison! The fifty-five works include settings for voices and lutes by famed composers of the period including Byrd, Weelkes, Gibbons and others. Dowland contributed this and one other devotional song to the collection, making these his last two published pieces. Though Dowland only set the first of nine stanzas, we’ve chosen to include Leighton’s more uplifting final verse to end on a more hopeful note.

A Pilgrim's Solace

Dowland’s “A Pilgrim’s Solace” is an interesting mashup of dark Lenten pieces and more lighthearted dances (like this one!). Come hear this fantastic program with Long & Away on Saturday night for more!

I love a lass... Alas, I love! - English madrigals and partsongs

These program notes were written by Elise Groves and Hilary Anne Walker for a program of English madrigals and partsongs presented by Tramontana in May 2015.

The term “madrigal” refers to two different forms, both Italian in origin. The 14th-century “madrigal” describes the poetic form favored by composers Jacopo da Bologna and Francesco Landini, among others. The first collection of 16thcentury “madrigals” was published in Rome in 1530, and following that publication, the madrigal quickly became the most popular secular genre of the 16thcentury. By the 17thcentury, the madrigal remained popular, but it had also taken on pedagogical importance. Those who studied composition with the great Italian masters would inevitably leave with a collection of madrigals in the Italian style. Because of this practice and the advances in printing that occurred somewhat simultaneously, collections of madrigals were quickly put into circulation not only in Italy but also throughout Europe.

In England, the influence of several Italian composers working in the court of Elizabeth I resulted in some early attempts to copy the Italian madrigal style, sometimes in Italian or in English translation of Italian madrigal texts. The text of “Lady, when I behold the roses” of John Wilbye is almost identical to that of Gesualdo’s “Son sì belle le rose” though the musical style is quite different. Musica Transalpina, published in 1588, was a collection of Italian madrigals translated into English, featuring pieces by Marenzio and Ferrabosco, among others.

English composers, armed with the developing English poetic forms, quickly took up the challenge to create a uniquely English madrigal. William Byrd, though better known for his instrumental and sacred music, experimented with secular genres, including the madrigal. Though he faced persecution as a recusant Catholic, Elizabeth I held him in high esteem and he wrote the first known madrigal in her praise – “This sweet and merry month of May” – in 1590. “Though Amaryllis dance in green” was originally composed as a consort song, but with the growing enthusiasm for madrigals, Byrd added text to all five parts and republished it in Psalms, Sonnets, and Songsof 1588. Byrd’s greatest contributions to the madrigal are not compositional in nature, but instead in his teaching of Thomas Tomkins, Thomas Morley, and possibly Thomas Weelkes. Tomkins would later dedicate “Too much I once lamented” to his “ancient and much reverenced Master Byrd.”

Some English madrigalists followed the Italian preference for more serious subject matter – courtly love, death, and pastoral imagery – and also followed the Italian tendency toward a more chromatic style with vivid word painting. Weelkes, Wilbye, and Tomkins were among these, exhibiting varying degrees of chromaticism and a definite preference for using not only counterpoint but also unusual harmonic shifts for expressive purposes.

Other English madrigal composers preferred lighter, more frivolous subject material, usually incorporating double entendre. Farmer’s “Fair Phyllis I saw sitting all alone”, in addition to being one of the best known madrigals of the English school, is an excellent example of this lighter style with clever word painting and the punning style which the English enjoyed so much. Orlando Gibbons, a colleague of Tomkins at the Chapel Royal, was more known for his sacred music than his secular compositions, but he turned to the madrigal for satire and social commentary. “The silver swan” published in Madrigals and Motets(1612) is a well-known and lovely example of the later English style, but the last line (“more geese than swans now live, more fools than wise.”) is sometimes viewed as his personal opinion of the state of musical composition in England.

Thomas Morley, another student of William Byrd, was more interested in the lighter aspects of the Italian style and tended to avoid overly dramatic effects and word painting. In his compositions, he can be accused of being more of a creative borrower than a composer, since almost all of his madrigals have roots in Italian model pieces. That aside, Morley’s setting of “It was a lover and his lass” is one of the very few known contemporary settings of Shakespeare, and Morley’s contributions to printing and publishing were integral to the popularity of the madrigal in England.

The Triumphs of Oriana was a collection of English madrigals edited by Thomas Morley and published in 1601 in honor of Elizabeth I. It was modeled on Il trionfo di Dori, an Italian collection from 1592, and included works by 23 different English composers, including Michael Cavendish, Thomas Tomkins, Thomas Morley, John Farmer, John Wilbye, and Thomas Weelkes. Every madrigal in the collection ends with the phrase “… then sang the shepherds and nymphs of Diana, ‘Long live fair Oriana’” taken from Croce’s Ove tra l’herbe e i fioriwhich originally appeared in Musica Transalpina, and was reworked by Morley as “Hard by a crystal fountain” for this publication. Following this model, Choral Songs in honour of Her Majesty Queen Victoria(1899) would later bring together 13 English composers, including Charles Villiers Stanford, to commemorate Queen Victoria’s 80thbirthday.

The madrigal enjoyed a relatively brief period of popularity in England compared to the rest of Europe, but madrigals were nonetheless a significant part of the larger tradition of part song writing for English composers. Part songs – songs for two or more voices without instrumental accompaniment – were an important secular genre long before the court of Elizabeth I. The court of her father, Henry VIII, included composer, poet, dramatist, and actor William Cornysh, and his quasi-round “Ah Robin, gentle Robin” is a lovely example of the pre-madrigal part song.

Eventually the madrigal was overtaken by the lute song, and no discussion of lute songs would be complete without mentioning John Dowland. Following several painful snubs by the English court, Dowland moved across the channel and spent the majority of his life in courts in Germany and Denmark. When Dowland published his books of lute songs, he improved upon the earlier system of part books by printing each song in the round. One page would show the melody line and the corresponding lute notation, and the facing page would show the other parts to be sung or played in the round, so that all performers could read from one book.

Later English composers continued the practice of writing part songs for both contemporary English poetry and poetry in translation. Robert Lucas Pearsall became a composer relatively later in life, after moving his family to Germany. There he was immersed in the German Cecilian movement, yet another in a long line of reforms which sought to make the music subservient to the text and contextual meaning in sacred compositions. Pearsall developed an affinity for Thomas Morley, and followed in his footsteps to borrow material, texts, and ideas for his own compositions, rather than focusing on his own compositional style. The tune of “Adieu! My Native Shore” was written by Renaissance composer Heinrich Isaac and harmonized by Senfl and Schein, but Pearsall adapted it with a few measures of his own composition to fit the lovely poetry of Lord Byron. Pearsall even borrowed from Morley himself for his setting of “Why weeps, alas, my lady-love”. While the composition seems to be Pearsall’s own original work, Morley’s own five-voice setting of the same text could not have been far from his mind. Pearsall’s use of suspensions in overlapping voices is also very reminiscent of older Italian madrigals, most notably those of Monteverdi, of which Morley was also fond.

In the early 20thcentury, Gerald Finzi, Gustav Holst, and others found great inspiration in the poetry of Robert Bridges, the poet laureate of England from 1913-1930. Finzi was an avid consumer of contemporary poetry; it is estimated his personal library contained more than 3,000 volumes of poetry, prose, and philosophy at the time of his death. Finzi’s use of rhythm and word painting is unique among later part song composers. While his pieces are certainly the most rhythmically difficult, he captures the intricate and complex rhythms of the English language better than perhaps any other composer, while still maintaining a beautiful flowing line. A wonderful example can be heard in his setting of Robert Bridges’ Clear and Gentle Streamwhere the traditional pealing tune of a clock tower is traded among voices when they sing about the “Minster tower”, thus the voices themselves become the tolling bell. Though Finzi had no formal musical training, he chose to study privately as a boy with Ernest Farrar, a student of Sir Charles Villiers Stanford.

Stanford, like Byrd before him, was a prolific composer, though his contributions to madrigals and part songs are perhaps less significant than his position as teacher to an entire generation of British composers, including Howells, Vaughan Williams, and Holst. As a faculty member at Cambridge University Musical Society, Stanford was responsible for not only raising the level of excellence, but also opening the Society’s doors to female voices.

Gustav Holst’s Four Songs, Opus 4, were composed while he was a student of Stanford at the Royal College of Music. The texts are a mix of English poetry, including a poem of Robert Bridges, and other languages in English translation; “Soft and Gently” is an English translation of the poem Leise zieht durch mein Gemütby Heinrich Heine. While Holst enjoyed a successful career as a composer and performer, he believed his role as a teacher was just as important. He dedicated 30 years of his life to teaching young women and firmly believed in making music more accessible for the amateur community to use for practical purposes like celebrations, ceremonies, and simple church services.

Holst’s emphasis on the amateur community reflects an important trend in the history of the English madrigal and part song. While Italian madrigals had been created specifically for professional singers to entertain their upper class patrons, English madrigals were written more with the entertainments of the growing merchant class in mind. Singing madrigals around a table became a popular pastime, and by the 20thcentury, madrigal societies and amateur choruses kept these pieces in the public performance sphere.

In addition to the fact that the English madrigal was intended for both amateur and professional performers, many of the composers were themselves trained in other fields. Pearsall was a lawyer who didn’t devote himself to studying composition until he was in his thirties and living abroad. Cavendish was a nobleman who occasionally composed as it suited him. Finzi had no formal musical degree, but proved himself to be a first rate composer. Because of this duality of professionals and amateurs, the English madrigal was frequently passed over by more “serious professionals” as being too trivial, simple, or frivolous. It has only been in the last several decades that English madrigals and part songs are once again being performed and appreciated for the incredibly expressive genre that they are – one which encompasses the full range of the human experience, from the most achingly painful to the silly to the most gloriously sublime.