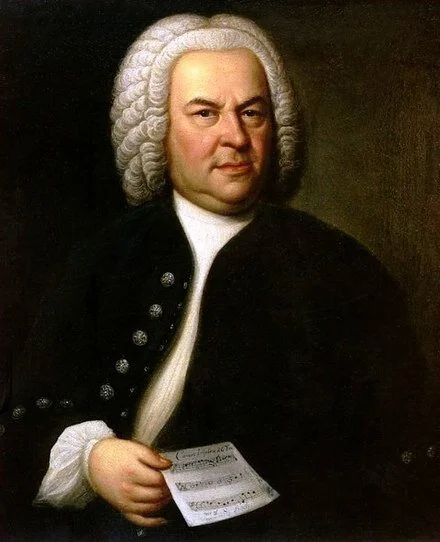

No better way to end 2018 than with Part 4 of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio (which roughly coincides with the New Year)!

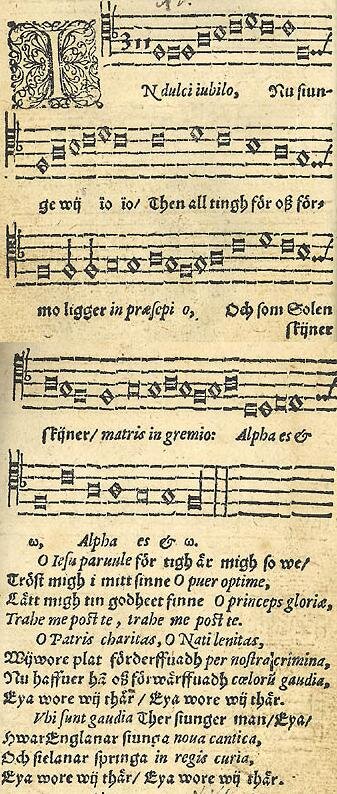

In dulci jubilo

The best Christmas Carols are the medieval ones! Last week’s Guggenheim concerts included Robert Pearsall’s luscious setting of “In dulci jubilo”, possibly my favorite carol of all. Merry Christmas!

Resonet in Laudibus

Michael Praetorius is a familiar name at this time of year, mainly for the carol “Lo how a rose e’re blooming”. His setting of Resonet in Laudibus for 4 soprano parts is on the program I’m singing tonight! Can’t come? Have a listen to Westminster Abbey’s version instead!

Musica ficta

It’s here!! Early Music Sources has an EXCELLENT video on musica ficta - possibly the most contentious of all early music topics. Also check out their videos on cadences and intabulations, because they’re referenced here.

Miryam's Esther

Baroque oratorio in Hebrew! My friends and colleagues in Miryam have a thrilling project planned for March! Read more about this amazing piece here, and save the dates!

H+H's Messiah

It’s a December standard, but how much do you really know about Handel’s Messiah? Check out these fantastic notes from Handel + Haydn Society and come hear us on Fri/Sat/Sun if you’re in Boston!

Enhanced Program Notes: Handel Messiah - Nothing to be compared

Bach's Church Music in Latin

Did you know Bach wrote liturgical music in Latin (and not just the Magnificat and B minor mass)? Early Music Monday takes a peek at this repertoire in advance of The Bach Project’s concert next Sunday!

Composers like to borrow

Composers never let a good idea go to waste. This week’s example of borrowing is Guerrero’s Missa de la batalla escoutez, based on Janequin’s madrigal “La Guerre” - a Spanish mass setting based on a French madrigal about the Battle of Marignano in 1515.

Cornysh "Salve Regina"

It’s always fun to revisit music from the Eton Choirbook - so complex, so demanding, and yet so rewarding at the same time! This week’s project is this gorgeous Salve Regina by William Cornysh.

Music for the Requiem

With Halloween and the commemorations of All Souls and All Saints later this week, Early Music Monday looks at the music for the Requiem, frequently performed in concerts, at Christian funerals, and used for dramatic moments in movies!